The Government of Uganda has confirmed the signing of an agreement with the United States of America on migration management, a move that has already sparked debate at home and abroad.

According to Mr. Vincent Bagiire Waiswa, the Permanent Secretary at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the arrangement will see Uganda temporarily host third-country nationals who are denied asylum in the U.S. but cannot be repatriated to their countries of origin.

“The agreement is part of our broader bilateral cooperation on migration management,” Bagiire said in a statement. “It is not a blanket arrangement but is subject to specific conditions. Individuals with criminal records or unaccompanied minors will not be accepted.”

Latest

US Celebrity Judge Frank Caprio Dies at 88 After Battle With Cancer

Uganda Secures €270 Million Afreximbank Loan to Fund Development Projects

Entebbe Airport Hits Record Passenger Numbers in July 2025

Police Recover Abandoned Gun in Kiboga

UPC Power Struggle Deepens as Adim Declares Himself Flagbearer

NRM Unveils Museveni’s Portrait and New Campaign Theme for 2026 Elections

FUFA Secures UGX 750M Medical Insurance Cover for 700 Players

Delegates Dump Gidudu, Rally Behind Ofwono Opondo

Traders Shut Shops in Kampala Over URA Taxes, Demand Musinguzi’s Resignation

Government, CEOs Gear Up to Position Uganda as Top Tourism Hub

UNEB Orders Public Display of 2025 Candidate Registers Until October

He further explained that Uganda has expressed preference that the migrants received under this arrangement should be from African countries. The detailed modalities of implementation are still being negotiated by both governments.

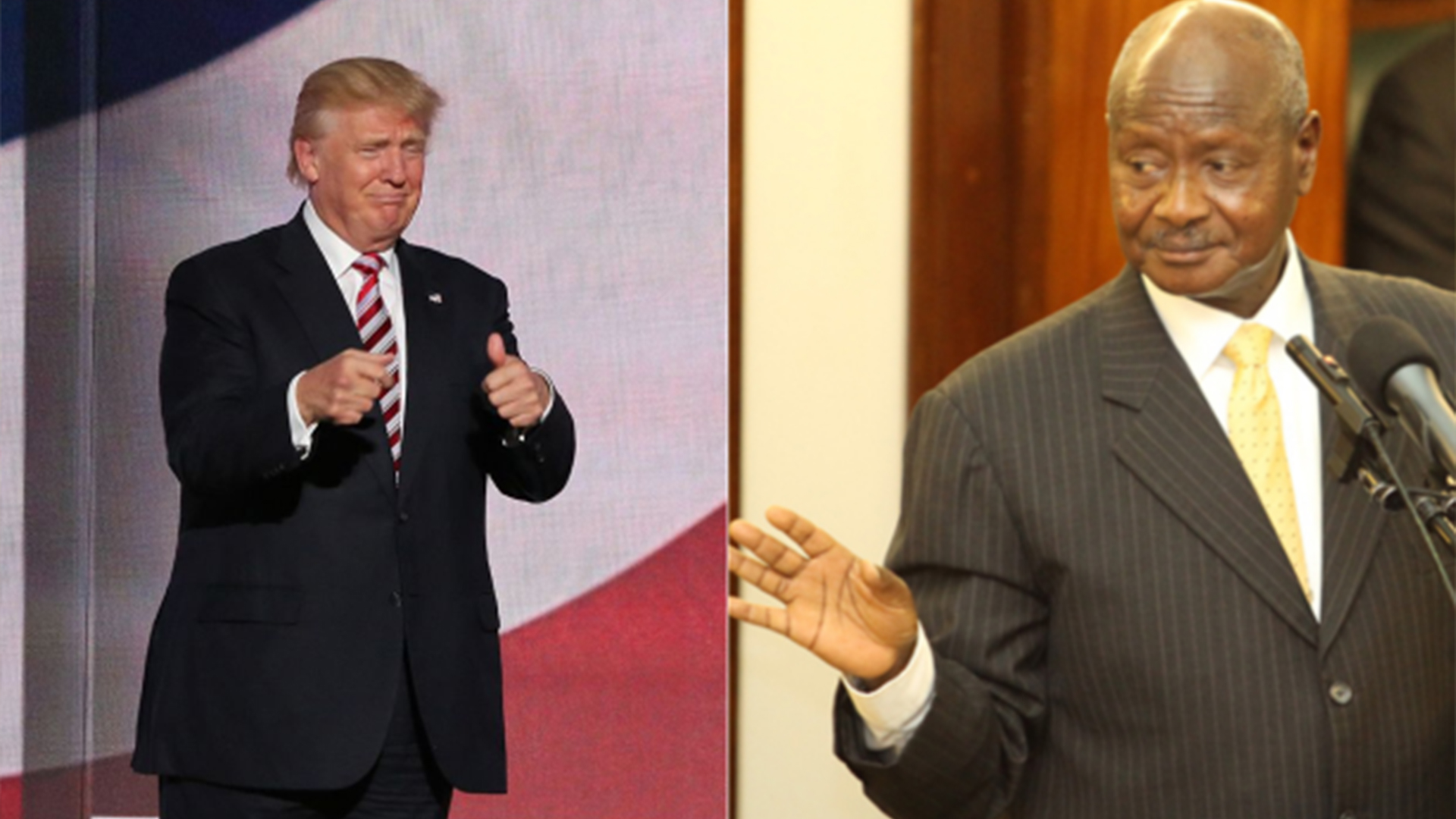

The deal, reportedly sealed following direct engagement between President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni and former U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration, underscores Uganda’s continued positioning as a strategic partner for the West on matters of migration and humanitarian response.

For years, Uganda has been hailed globally for its open-door refugee policy, hosting more than 1.5 million refugees mainly from South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and other conflict-affected countries. However, critics argue that hosting third-country nationals rejected by the U.S. could stretch Uganda’s already burdened resources and raise social integration challenges.

Civil society groups and opposition politicians have called for greater transparency on the agreement, demanding that government clearly explain the financial, security, and humanitarian implications for the country.

“This is not just a diplomatic gesture. Ugandans deserve to know how many people we are talking about, how long they will stay, and who will foot the bill,” said one Kampala-based migration policy analyst.

The U.S. government has framed the arrangement as part of its global migration strategy, designed to manage asylum claims more efficiently while working with trusted partners to protect vulnerable populations.

With both governments still ironing out the implementation framework, questions remain about funding, oversight, and the exact categories of individuals who may be relocated to Uganda.?